Introduction

These days, when we think of nation-state level damage, we immediately think of the nation-state level actor that must be responsible for it. While most attacks against a nation’s sensitive networks are indeed the work of other governments, the truth is that there is no magic shield that prevents a non-state sponsored entity from creating the same kind of havoc, and harming critical infrastructure in order to make a statement.

In this piece, we present an analysis of a successful politically motivated attack on Iranian infrastructure that is suspected to be carried by a non-state sponsored actor. This specific attack happened to be directed at Iran, but it could as easily have happened in New York or Berlin. We’ll look at some of the technical details and expose the actor behind the attack — thereby linking it to several other politically motivated attacks from earlier years.

Key Findings

- On July 9th and 10th, 2021 Iranian Railways and the Ministry of Roads and Urban Development systems became the subject of targeted cyber attacks. Check Point Research investigated these attacks and found multiple evidence that these attacks heavily rely on the attacker’s previous knowledge and reconnaissance of the targeted networks.

- The attacks on Iran were found to be tactically and technically similar to previous activity against multiple private companies in Syria which was carried at least since 2019. We were able to tie this activity to a threat group that identify themselves as regime opposition group, named Indra.

- During these years, the attackers developed and deployed within victims’ networks at least 3 different versions of the wiper dubbed Meteor, Stardust, and Comet. Judging by the quality of the tools, their modus operandi, and their presence on social media, we find it unlikely that Indra is operated by a nation-state actor.

- A technical analysis of the tools, as well as the TTPs used by the underlying actor, are thoroughly described in this article. We share with the public Yara rules and a full list of indicators of compromise.

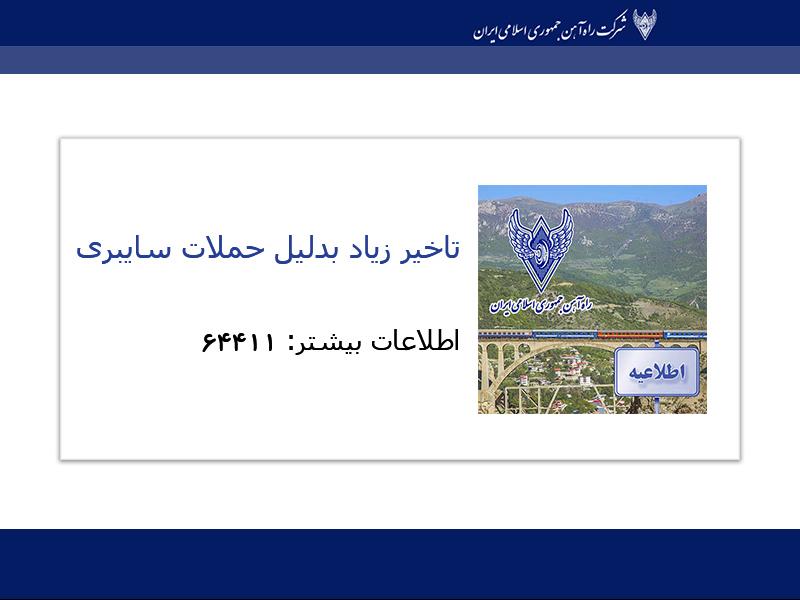

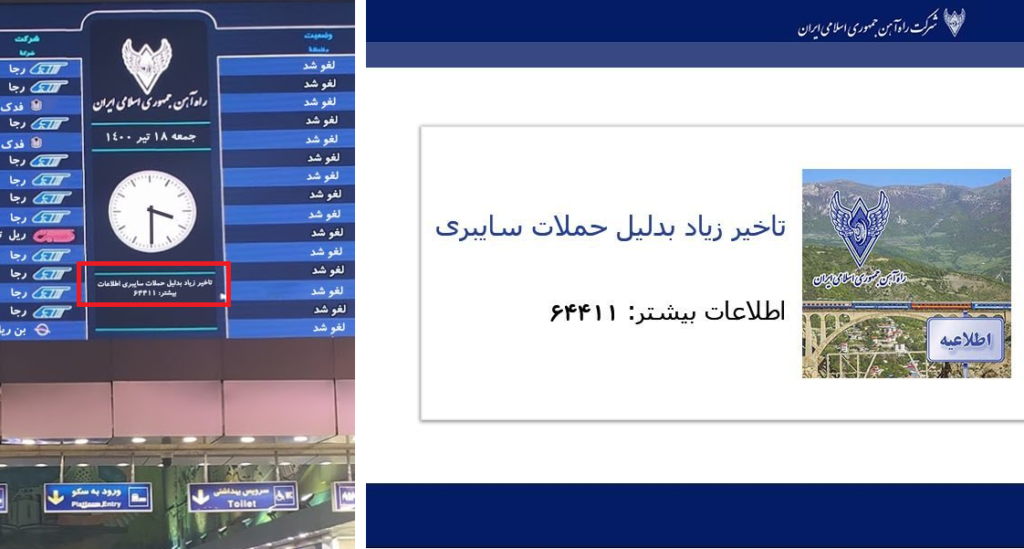

On Friday, July 9th, Iran’s railway infrastructure came under cyber-attack. According to Iranian news reports, hackers displayed messages about train delays or cancellations on information boards at stations across the country, and urged passengers to call a certain phone number for further information. This number apparently belongs to the office of the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

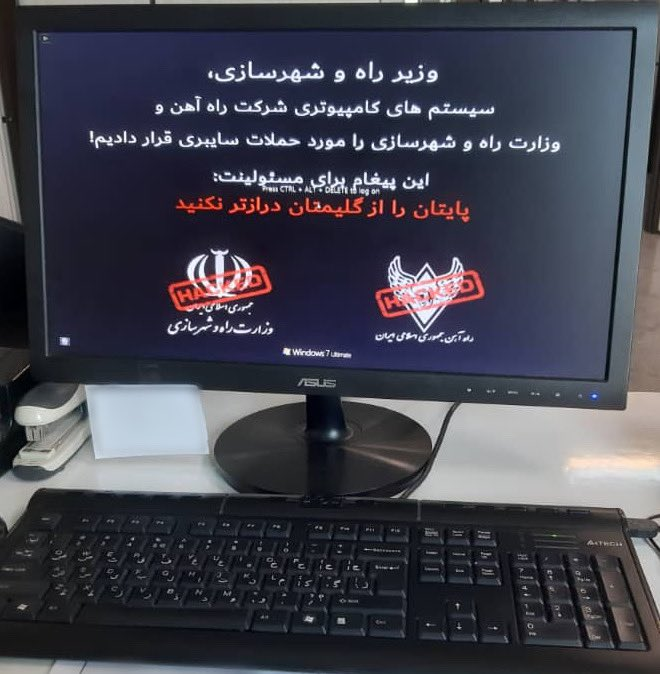

The very next day, July 10th, websites of Iran’s Ministry of Roads and Urbanization reportedly went out of service after another “cyber-disruption”. Iranian social media spread the photos of a monitor of one of the hacked computers, where the attackers took responsibility for both consecutive attacks.

A few days later, Iranian cybersecurity company Amnpardaz Software published a short technical analysis of a piece of malware supposedly related to these attacks, dubbed Trojan.Win32.BreakWin. Based on the information published, Check Point Research Team retrieved the files from publicly available resources and conducted a thorough investigation of them. The findings shared in this report were reviewed and evaluated by journalists and fellow researchers from other security vendors. During this time, SentinelOne released a report based on Amnpardaz’s analysis.

In this article, we first analyze the artifacts left by these attacks. Based on this analysis, we uncover a set of similar tools previously used in other operations during 2019-2020: carried against multiple targets in Syria, they did not attract much public attention at the time. We then share some insights into the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) of the underlying actor, which self-identifies as “Indra” and, according to some Iranian sources, may have ties to hacktivist or cybercriminal groups.

Hunting for the files from the Iranian hack

With Amnpardaz’s threat database as our starting point, we searched for files with similar names and functionality. The search led us to dozens of files, all uploaded from the same two sources located in Iran. Even though we weren’t able to find all the mentioned artifacts, we recovered most of the execution flow as described in Amnpardaz’s report.

The execution flow is heavily based on multiple layers of archives and Batch scripts. When detonated, they:

- Attempt to evade anti-virus detection

- Destroy the boot configuration data

- Run the final payloads that aim to lock and completely wipe the computers in the network.

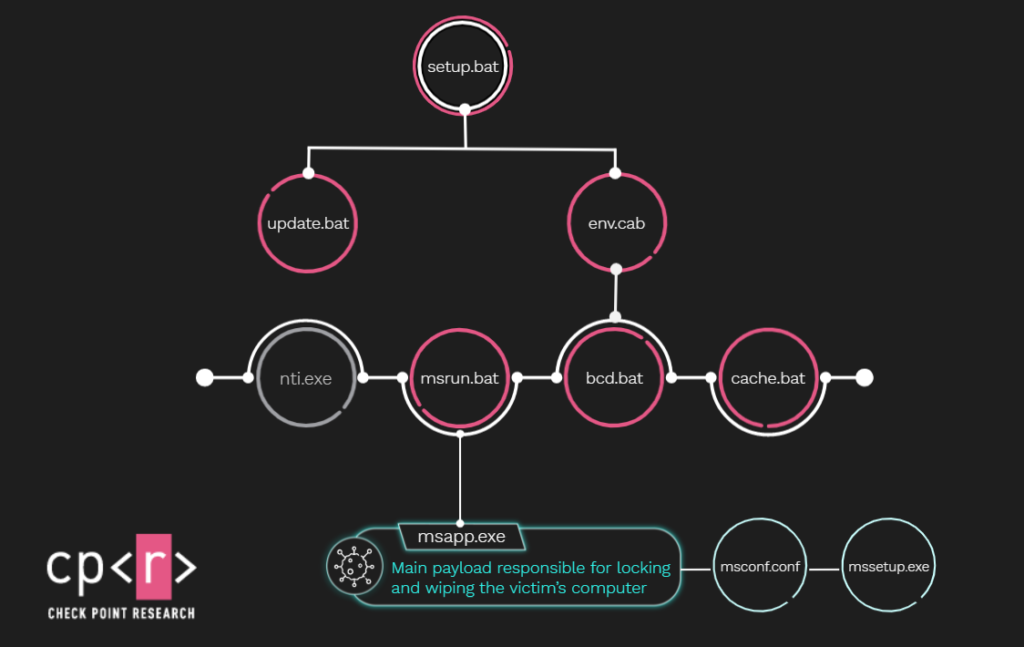

The execution starts with pushing a scheduled task from the AD to all the machines via group policy. The task name is Microsoft\Windows\Power Efficiency Diagnostics\AnalyzeAll and it mimics the AnalyzeSystem task performed by Windows Power Efficiency Diagnostics report tool. The subsequent chain of .bat files and archives is intended to perform the following operations:

- Filter the target machines:

setup.batfirst checks if the hostname of the machine is one of the following:PIS-APP,PIS-MOB,WSUSPROXYorPIS-DB. If so, it stops the execution and deletes the folder containing the malicious script from this machine.PISin the hostnames stands for Passenger Information System, which is usually responsible among others for updating the platform boards with actual data, so attackers made sure their message to the Iranian public will be displayed properly. - Download the malicious files onto the machine: the same batch file downloads a

cabarchive namedenv.cabfrom a remote address in the internal network:\\railways.ir\sysvol\railways.ir\scripts\env.cab. The use of specific hostnames and internal paths indicates the attacker had prior knowledge of the environment. - Extract and run additional tools:

update.bat, which was extracted and started bysetup.bat, uses the passwordhackemallto extract the next stages:cache.bat,msrun.batandbcd.bat. - Disconnect the machine from all networks: the cache.bat script disables all the network adapters on the machine with the following command:

powershell -Command "Get-WmiObject -class Win32_NetworkAdapter | ForEach { If ($.NetEnabled) { $.Disable() } }" > NUL - Perform Anti-AV checks: the same

cache.batscript also checks if Kaspersky Antivirus is installed on the machine and if not, it adds all the files and folders related to the attack to the Windows Defender exclusion list and proceeds with the execution. - Corrupt the boot:

bcd.batis used in order to harm the boot process. First, it tries to override thebootfile with new content and then deletes the different boot identifiers using Windows built-in BCDEdit tool:for /F "tokens=2" %%j in ('%comspec% /c "bcdedit -v | findstr identifier"') do bcdedit /delete %%j /f - Remove all the traces: the same

bcd.batin addition to boot override also removes Security, System and Application Event Viewer logs from the system usingwevtutil. - Unleash the main payload: The

msrun.batscript is responsible for unleashing the Wiper. It moves wiper-related files to “C:\temp” and creates a scheduled task namedmstaskto execute the wiper only once at 23:55:00.

Analysis of the main payload — The Wiper

The main payload of the attack is an executable named msapp.exe, and its purpose is to take the victim machine out of service by locking it and wiping its contents. Upon execution, the malware hides this executable’s console window to decrease the suspicion of vigilant victims.

Wiper configuration file

The wiper will refuse to function unless it is provided a path to an encrypted configuration file msconf.conf as a command-line argument. The configuration file allows some degree of flexibility during the execution of the payload and gives the attacker the ability to tailor the attack to specific victims and systems. A helper script to decrypt the configuration file is available in Appendix C.

The configuration format used supports multiple fields, which jointly hint at this binary’s role in the attack.

Supported Configuration Fields

| auto_logon_path | log_file_path |

| cleanup_scheduled_task_name | log_server_ip |

| cleanup_script_path | log_server_port |

| is_alive_loop_interval | paths_to_wipe |

| locker_background_image_jpg_path | process_termination_timeout |

| locker_background_image_bmp_path | processes_to_kill |

| locker_exe_path | self_scheduled_task_name |

| locker_installer_path | state_encryption_key |

| locker_password_hash | state_path |

| locker_registry_settings_files | users_password |

| log_encryption_key | wiping_stage_logger_interval |

Not all these fields were actually used in the configuration file of the wiper targeting the Iranian networks, which might suggest that the tool was not created specifically for this attack (or otherwise, that its design fell victim to premature optimization).

If the configuration is parsed successfully, the program writes the string "Meteor has started." to an encrypted log file, suggesting that the internal name of the malware is “Meteor“. As we will see later on in this article, another name was used in previous attacks. Throughout the entire execution of the malware, it keeps logging its actions to this same encrypted log file. These detailed debug logs make it easier to analyze the malicious binary and understand its workflow. Appendix C contains a helper script to decrypt the log file.

Configuration steps

The malware next sets out to prevent the victim from stopping the ongoing infection. First, the machine is removed from the Active Directory domain by using WinAPI or WMI. This makes it harder to remotely push any remediation tools to the infected machines. Next, the malware proceeds to corrupt the computer’s boot configuration: in versions of Windows prior to Windows 7, the malware overrides the c:\boot. ini file; in Windows 7 and above, it deletes the BCD entries. Finally, the malware changes the password of the local users. In the files analyzed, all the passwords chosen by the actor have the same pattern: Aa153![random sequence], for example Aa153!rHrrdOvpCj or Aa153!IRro3d2JYm.

When all the above is said and done, the user will not recover access to their machine easily. At this stage the malware disables the Windows screen saver, then changes both the desktop wallpaper and the lock screen images to a custom image. These are the pair of identical JPEG and BMP images presenting the logo of Iran’s Railways and the message similar to the one displayed on the platform boards of different railway stations in Iran:

Something about this “long delays due to cyber attacks” message just tickles our fancy, and betrays a somewhat surrealistic sense of humor on the attackers’ part. They could have written anything, but they chose that.

With the above done, the malware logs off all users and executes a small program — a “locker” — in a new thread. The path to the locker file named mssetup.exe is retrieved from the configuration. mssetup.exe will prevent the user from interacting with the machine by blocking inputs from the keyboard and mouse devices. Finally, before moving to its main cause — wiping the system — the malware creates a scheduled task that assures its own persistence in the system. The scheduled task will be executed every time the system starts.

As an aside, there is an extra step that didn’t take place in this specific attack; the malware is supposed to terminate all processes named in a processes_to_kill list specified in the configuration file. As it happens, the configurations used in the attacks against the Iranian targets did not contain this list, and so no processes were terminated. We will later show configuration files from previous attacks that did indeed use this feature.

Wiper functionality

Internally, this part is called "Prefix Suffix wiper". As its name suggests, the malware gets a list of prefixes and suffixes from the configuration file and wipes the files that are matched by this rule. Another string in the malware — "Middle Wiper" — was probably used by this malware in the past in order to wipe the files that contain some unique substrings.

The wiping procedure itself is pretty simple. First, the malware goes over the files and directories from the paths_to_wipe config, fills them with zero-bytes instead of their real content, and then deletes them.

After the wiping procedure, the malware tries to delete the shadow copies by running the following commands: vssadmin.exe delete shadows /all /quiet **and **C:\\Windows\\system32\\wbem\\wmic.exe shadowcopy delete. Finally, the malware enters an infinite loop where it sleeps based on the is_alive_loop_interval value from the configuration file and writes "Meteor is still alive." to the log in every iteration.

If all this rings familiar to you, it should; it’s all straight out from the ransomware playbook — except this isn’t ransomware, which requires delicate orchestration of public-key and private-key cryptography to make the machine ultimately recoverable; this is Nuke-it-From-Orbit-ware. It’s a one-way trip.

Connecting the files to the recent attacks against Iranian targets

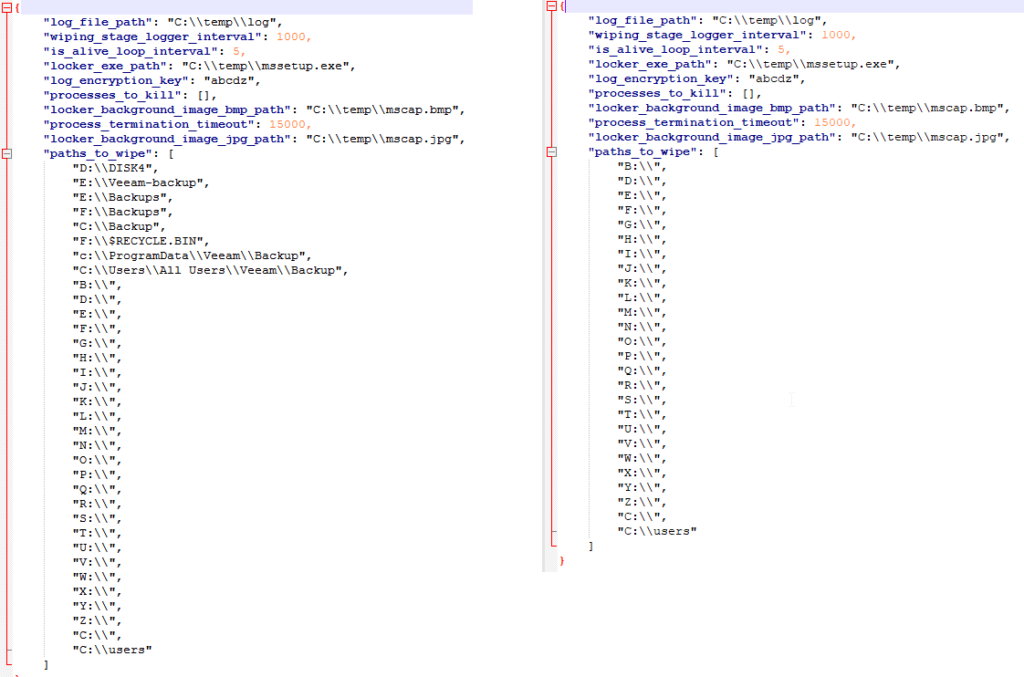

Our analysis of the files aligns with the analysis conducted by Amnpardaz. The flow of the attack is almost identical; the files have similar structure, the same names and the same functionality. With that said, there are still some differences. For example, the update.bat script that we analyzed is not used by the earlier variants, which instead execute nti.exe — an MBR infector based on the one used by NotPetya. Another example is a slight difference between the configuration shown in the Amnpardaz report and the configuration that we analyzed. The minor differences are in the paths_to_wipe key:

Some of the files we’ve found contain artifacts that tie them to the attack against Iran Railways. One of them is the image the attackers used when replacing the victim’s wallpaper and lock screen image. As we mentioned before, the text that is showed is identical to the text the attackers displayed on the train stations.

Other pieces in the files we analyzed contain names and other artifacts from Iran Railways’ internal network, including computer names and internal Active Directory object names. For example, the envxp.bat (67920ff26a18308084679186e18dcaa5f8af997c7036ba43c2e8c69ce24b9a1a) file delivered a payload using a shared directory under the \\railways.ir machine:

This can suggest that the attackers had access to the system prior to unleashing the wiper. An article by the IRNA also mentions that experts who analyzed the attacks believe that they took place at least one month before being identified.

Attacks Against Companies in Syria

Hunting for more files

Equipped with the information gathered so far, we went for a hunt to find more samples. Specifically, to find whether the attack on the Iranian targets was the first time that the attackers utilized these tools. Our queries quickly yielded results — files that were uploaded to Virus Total by three different submitters located in Syria. The files seemed to belong to three separated incidents and were uploaded to VT in January, February and April 2020, more than a year before the recent attacks against the entities in Iran.

The main payloads (d71cc6337efb5cbbb400d57c8fdeb48d7af12a292fa87a55e8705d18b09f516e, 6709d332fbd5cde1d8e5b0373b6ff70c85fee73bd911ab3f1232bb5db9242dd4, and 9b0f724459637cec5e9576c8332bca16abda6ac3fbbde6f7956bc3a97a423473) appear to be the early versions of the Meteor wiper that was used against the targets in Iran. Similar to Meteor, they also contain multiple debug strings, which disclose the internal name of these versions of the wiper — Stardust and Comet. Out of these two versions, Comet is the older one, compiled back in September 2019. While we have the complete execution flow of the two attacks that utilized Stardust, we only have a partial view of the one where Comet was used. For this reason, we will focus more on the execution chain of Stardust.

Unlike the recent attacks where the Batch files were used during early infections stages, these Stardust executions are based on multiple VBS scripts. What’s more, these scripts contain valuable information — the identities of the attacks’ targets.

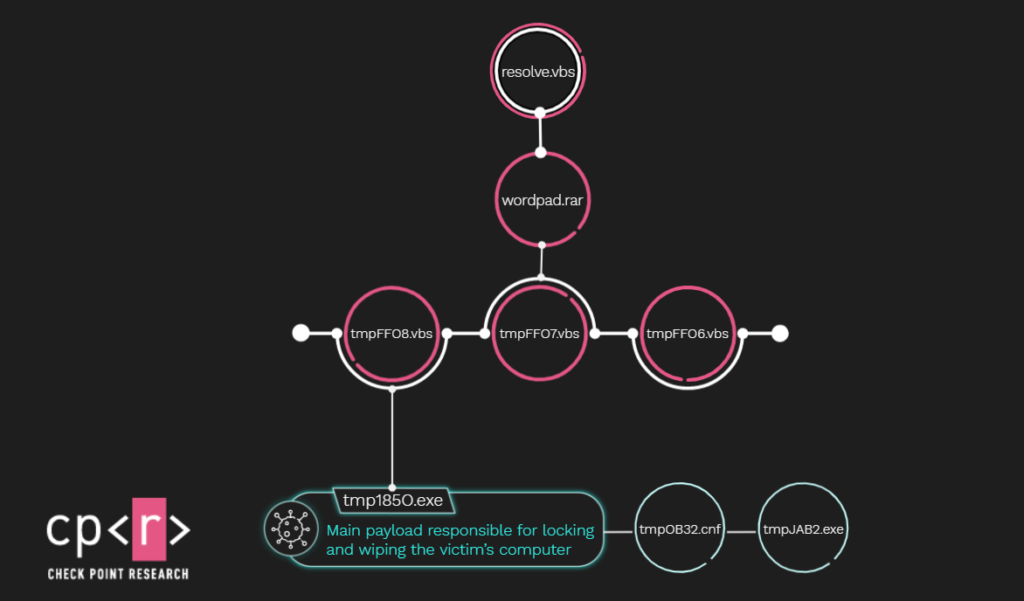

The execution flows of both attacks leveled at Syria in which Stardust was deployed are very similar and thus they will be described together. The initial payload that runs on the victim’s machine appears to be a VBS script resolve.vbs that extracts a password-protected RAR archive to the working folder C:\\Program Files\\Windows NT\\Accessories\\. This RAR contains another RAR file and three other VBS files. Then, the resolve.vbs script runs the extracted scripts in the following order:

- The first script iterates over the installed programs and checks if Kaspersky Antivirus is installed. If so, it tries to uninstall it using hardcoded domain credentials.

- The second script starts by checking if Kaspersky’s

avp.exeprocess is running, and if so it tries to remove the Kaspersky license. - The last script extracts the second-stage RAR archive and runs an executable file that the archive contains. This stage is the earlier mentioned

Stardustvariant of the wiper.

During the execution of these scripts, several requests are made to a server in order to trace the different steps of the execution. These are GET requests to a URL with the following pattern, where C&C IP is different between the attacks.

where:

hn= the Host Namedt= the Current Date and Timest= the Current Steprs= the Kaspersky AV running information

Evolution of a Wiper

The wiper was the final payload used in all four incidents. The different names — Meteor, Stardust or Comet, depending on the version — weren’t the only difference between the variants. During the evolution of 3 generations, the attackers introduced several changes in the tool, some are more significant than others. Key changes between the different variants of the wiper are explained below.

Comet is the earliest variant we have, and it might as well be the first to be created. Unlike Stardust and Meteor, it does reference and makes use of all the strings and features inside it. The others contained the artifacts, while the code itself did not utilize them. Comet has a Kill Switch based on values from the config file including the server IP, port, URL path, and a number of requests to perform before aborting. It tries to connect to the server and if it doesn’t get a response, or the response status is not 200 OK it aborts. In addition, the oldest variant creates a user as an Administrator using NetUserAdd and NetLocalGroupAddMembers APIs. Then it disables the first logon animation, as well as the first logon Privacy Settings screen. Finally, it adds itself to the auto logon based on a path it has in its configuration.

Unlike Meteor, Stardust and Comet do not override the boot. ini file during their attempts to corrupt the boot configuration. This feature, only relevant for Windows versions prior to Windows 7, only exists in the Meteor version. The earliest version, Comet, does not contain the ability to corrupt boot configurations at all.

The content Meteor writes to boot. ini.

Stardust and Comet use “Lock My PC 4”, a tool that restricts unauthorized use which used to be publicly available. After running the Lock My PC program, they remove the “hkSm” registry value to delete the generated lock password, then delete the uninstaller of the tool to make it harder to recover system functionality. This functionality is not used in Meteor, even though it has related artifacts.

The configuration files used in the attacks against the Syrian targets utilized more fields than the configurations that were used against the Iranian targets. These fields include process_to_kill, paths_to_wipe, log_server_ip, and log_server_port. Their content sheds the light on the targets of these operations and indicates that the attacker had access to the targeted networks prior to deploying the final attack.

The log_server_ip and log_server_port configuration fields are used by the Stardust wiper to send a Base64-encoded log file to the remote server. The request is sent via HTTP POST to the data.html resource on the server. The configs that we obtained contain different values for the servers, disclosing two IP addresses that were used by the attackers.

Who are the targets?

Multiple artifacts that were inspected during the analysis of these two Stardust operations in Syria point to the targeted companies — Katerji Group and its related company Arfada Petroleum — both located in Syria. First, the names of these companies appear in the VBS files as the parameters for the commands they executed to disable the Kaspersky AV. Another indication is the paths listed under the paths_to_wipe field in both configurations. These paths contain a list of user names, including the domain administrators of these two companies.

Meet Indra

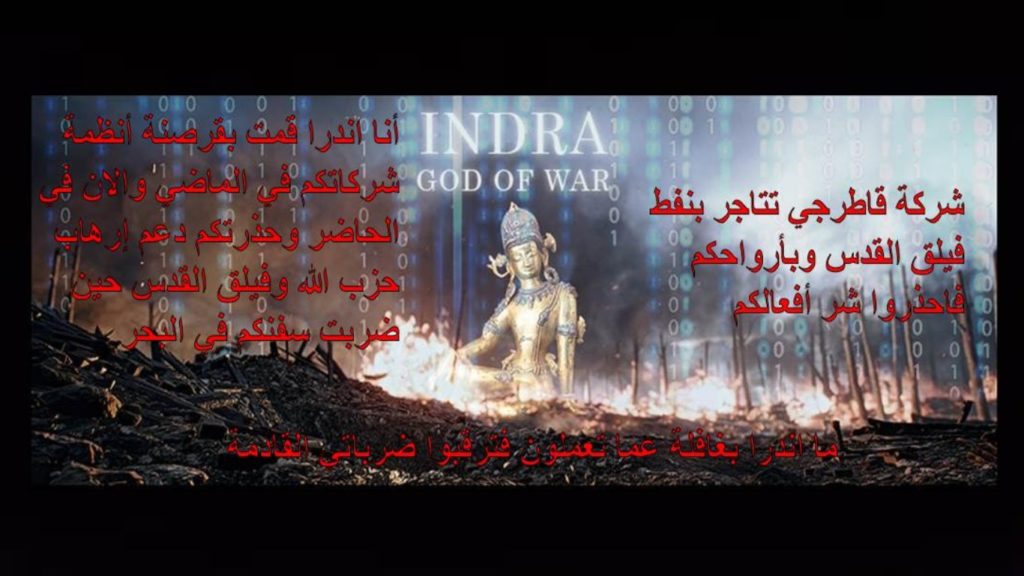

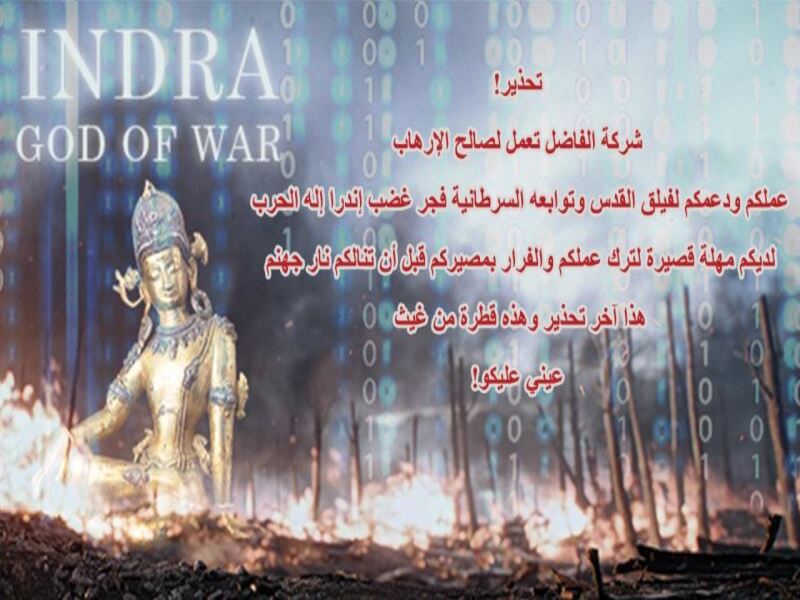

Our scrutiny revealed not only the attacks’ targets, but also the identity of the group behind these operations — a group that calls itself “Indra” after the Hindu God of War. In fact, Indra did not try to hide that they are responsible for these operations, and left their signature in multiple places.

The image that was displayed by the attackers on the victims’ locked computers announces “I am Indra” and takes the responsibility for the attacks on Katerji group.

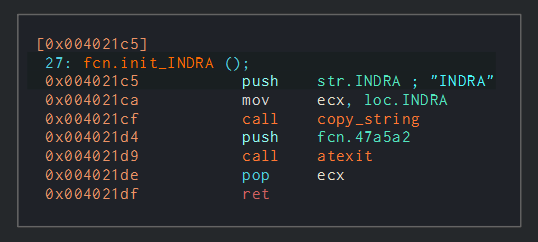

In addition, all samples of the wiper but Meteor, contain multiple occurrences of the string “INDRA”. It is used by the Comet variant as the username of a newly created Administrator account. On Stardust though, it serves as an inert artifact, and is not involved in execution.

We wondered whether this Indra attack group has any online presence, and in fact, they do. They operate multiple social network accounts on different platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, Telegram, and Youtube. Among other information, the accounts contain the disclosure of the attacks on the aforementioned companies:

Surveying this social network activity, one can get an idea of the group’s political ideology and motive for the attack, and even hear about some of the group’s previous operations.

The title of INDRA’s official twitter account states that they are “aiming to bring a stop to the horrors of QF and its murderous proxies in the region” and they claim to be very focused on attacking different companies who allegedly cooperate with the Iranian regime, especially with the Quds-Force and Hezbollah. Their posts are all written in English or Arabic (both don’t seem to be their native language), and most talk about opposing terror or offer document leaks from the various different companies that fell victim to the group’s attacks due to suspected ties to the Iranian Quads Force.

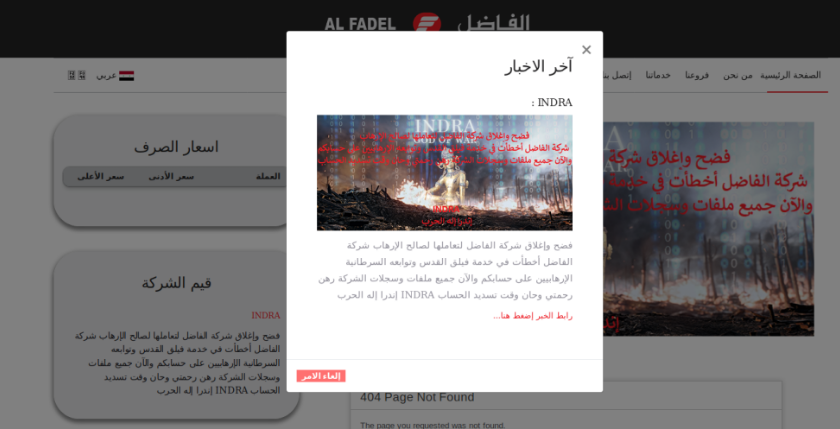

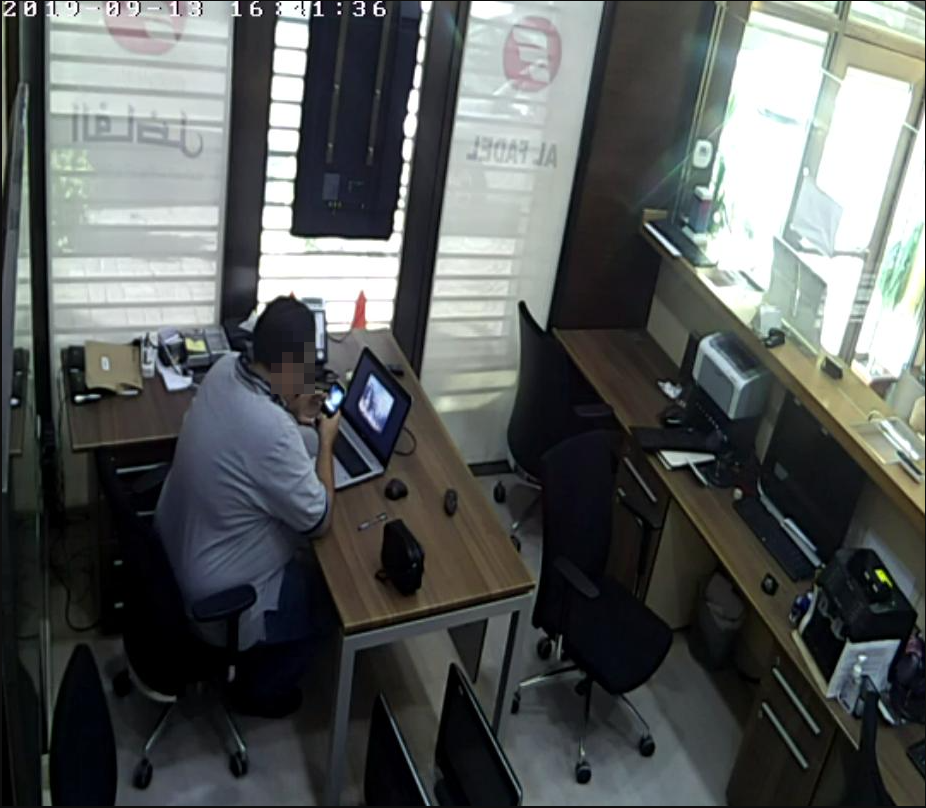

In their first message, posted September 2019, INDRA claims to have carried out a successful attack against the company Alfadelex, demolished their network, and leaked the customers’ and employees’ data. One of the pictures that were posted by Indra from the hack against Alfadelex shows a webcam photo of a person sitting in front of a computer as they were watching the image we found used by Comet on their screen (one can only imagine how they felt at that moment). Another image, displayed on Alfadelex’s website, has the same background as the other images we found used in the attacks against Alfadelex, Katerji, and Arfada.

This background image also appears as the cover photo of Indra’s Twitter and Facebook accounts.

Previous Indra Operations

Summing up the social network activity of Indra, the actors claim to be responsible for the following attacks:

- September 2019: an attack against Alfadelex Trading, a currency exchange and money transfer services company located in Syria.

- January 2020: an attack against Cham Wings Airlines, a Syrian-based private airline company.

- February 2020 and April 2020: seizure of Afrada’s and Katerji Group’s network infrastructure. Both companies are situated in Syria as well.

- November 2020: Indra threatens to attack the Syrian Banias Oil refinery, though it is not clear whether the threat was carried out.

Around November 2020, all of Indra’s accounts fell silent. We weren’t able to find evidence of any additional operations until this latest one.

Connecting Indra to the Attacks on Iranian Targets

The series of attacks on Syrian targets in 2019 and 2020 bears multiple similarities to the campaigns against the Iranian networks. These are similarities in the tools, the Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTP), as well as in the highly targeted nature of the attack, and they make us believe that Indra is also responsible for the recent attacks in Iran.

- The attacks are all directed against Iranian-related targets, whether it is Iran Railways and Iran’s Ministry of Roads in 2021, or Katerji, Arfada, Alfadelex, and other Syrian companies targeted in 2020 and 2019. Indra’s tweets and posts make it clear that they are targeting entities that they believe have ties with Iran.

- The multi-layered execution flow in all the attacks we analyzed — including the recent attacks against Iranian targets — uses script files and archive files as their mean of delivery. The scripts themselves, although they are of different file types, had almost the same functionality.

- Execution flow relies on previous access and recon info about the targeted network. In case of Iranian intrusion, the attackers knew exactly which machines they need to leave unaffected in order to deliver their message publicly; furthermore, they had access to the railway’s Active Directory server which they used to distribute the malicious files. Another indication for the reconnaissance done by Indra is the screenshot they took from Alfadelex’s Web Camera, showing the office with an infected PC.

- The wiper is the final payload deployed on the computers of the victims in all the aforementioned attacks. Meteor, Stardust, and Comet are different versions of the same payload, and we do not have an indication that this tool was ever used by other threat actors.

- The actor behind the attacks we analyzed did not try to keep their attack a secret. They shared messages and displayed pictures announcing the attacks. In the attacks against the Iranian targets, these messages were displayed not only on affected computers but also on the platform boards.

Unlike their previous operations, Indra did not publicly take responsibility for the attacks in Iran. This might be explained by the seriousness of the new attacks, as well as their impact. While the attacks we inspected in Syria were carried against private companies, the attacks against Iran Railways and the Ministry of Roads and Urbanization targeted official Iranian entities. Moreover, the attacks in Syria received little media attention, whereas the attacks against the Iranian government were covered extensively all over the world and reportedly caused the Iranians some amount of grief.

Conclusion

By carrying out an analysis of this latest attack against Iran, we were able to reveal its convoluted execution flow as well as 2 additional variants of the final ‘wiper’ component. These tools, in turn, were used previously in attacks against Syrian companies, for which the threat actor Indra took responsibility officially on their social media accounts. While Indra chose not to take responsibility for this latest attack against Iran, the similarities above betray the connection.

There are two lessons to be learned from this incident.

First, anonymity is a one-way street. Once you sacrifice it to reap PR and obtain some sweet likes on Twitter, it is not so easily recovered. You can stop broadcasting your actions to the entire world and you might think that you’ve gone under the radar, but The Internet Remembers, and given enough motivation, it will deanonymize you, even if you’re a badass hacktivist threat actor.

Second, that we should be more worried about attacks that are entirely possible but “clearly aren’t going to happen” according to the calculus of prevailing common wisdom. With all the trouble caused by cybercrime, hacktivism, nation-state meddling and so forth and so on, the extent and sophistication of attacks in general is still a fraction of its complete potential; oftentimes, threat actors don’t do X, Y, Z even though they perfectly well could, and we come to rely on this truancy like it were a law of nature.

Cases like this, where said threat actors go ahead and do X, Y, Z, ought to raise our collective level of anxiety. As we said in the opening statement, this attack happened in Iran, but next month an equivalent attack could be launched by some other group targeting New York, and Berlin the month after that. Nothing prevents it, except threat actors’ limited patience, motivation and resources, which — as we’ve clearly just seen — are sometimes not so limited after all.

Appendix A – Indicators of Compromise

Samples:

C&C servers:

Appendix B – Yara Rules

Comments

Post a Comment